A city famous for its ethnic and religious tensions may undergo more unrest within the next few weeks as decision is set to be made over the ownership of a long-forgotten medieval cellar that for centuries has been filled with rubbish.

The cellar, which dates to at least the 12th century, lies in Jerusalem, and is claimed by both a Palestinian Muslim shopkeeper and Egyptian Coptic Christians who have responsibility over part of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, one of Christianity's holiest site.

The legal battle over the centuries-old vaulted stone cellar has been festering for 14 years in the heart of the Holy City. It has as many twists and turns as the Old City, a maze of narrow streets and intrigue, and features top Middle East political players.

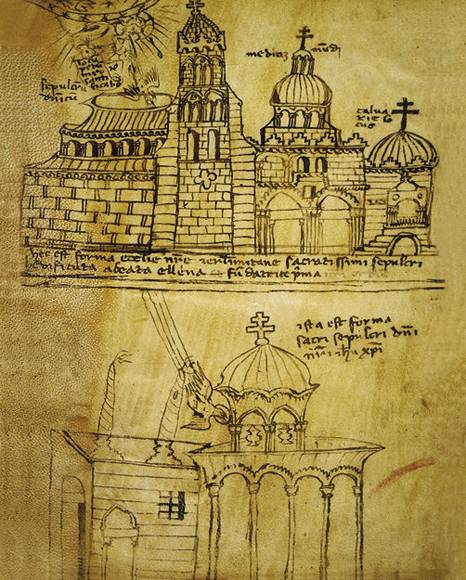

Antonios al-Orshaleme, general secretary of the Coptic Orthodox Patriarchate in Jerusalem, insists the basement is holy ground and was once part of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, revered by most Christians as the site where Jesus Christ was crucified and buried.

Orshaleme says the vast cellar, which runs under both the patriarchate and the grocery store, had been a church at least as long as the Holy Sepulchre, but remains vague as to when it was last used as such.

The church was built in the fourth century. Its destruction seven centuries later provided an impetus for the Crusades. It was rebuilt in 1048 following agreement between the Byzantine Empire and the region's Muslim rulers.

"Here is a monastery, below is also a monastery," says Orshaleme.

Not so, says lawyer Reuven Yehoshua, who represents storekeeper Hazam Hirbawi. "For 800 years this cellar was used as a garbage dump," says Yehoshua.

The entrance to the basement, which can be seen from above through a mesh of wire, is cluttered with a jumble of discarded objects. Yehoshua points to a 1921 survey that describes the basement as being "disgusting" and filled with cesspools. "This is what they say is a holy place?" Yehoshua asks.

The modern dispute started in 1996 when Hazam Hirbawi was sent by his father to the cellar to pick up a stone he needed to repair a wall in the building, only to find 10 Copts digging and clearing out mud and rubble.

"I asked what they were doing. They said: 'We're fixing our place'," said Hirbawi. "We kicked them out," he adds.

According to Orshaleme they were innocently carrying out work in the church-cellar when Hirbawi and others attacked them with knives, injuring a monk.

Immediately after that incident, six armed men in civilian clothes arrived at Hirbawi's home in a northern Jerusalem neighborhood. They said they were from the Palestinian Authority's Preventive Security forces and demanded that Hirbawi accompany them. When he resisted, one of them fired two bullets into the floor.

Hirbawi was taken to Ramallah, where he learned the metropolitan had been using his Egyptian connections: Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat had promised Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak that he would intervene on the Copts' behalf.

"Without really looking into the story, Arafat said this would be a gift from the Palestinians to the Egyptians," says Hirbawi's son, Hazam, who says the Palestinian interrogators tried to persuade his father to give up the cellar "for better or worse" - but he refused.

The dispute rapidly snowballed and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who served a first term at the time, sent forces to surround Ramallah. The elder Hirbawi was released three days later and took the issue to the Israeli authorities.

Yehoshua, and attorneys Ovadia Gabbay and Michael Deborin, representing the Coptic metropolitan, are now putting the final touches on their arguments. Both sides have enlisted archaeologists, historians and theologians.

Yehoshua conducted in-depth research detailing the cellar's incarnations over the past 3,000 years. "History is my hobby," he says. "It was fascinating to do the detective work on the developments in such a sensitive place in Jerusalem."

The Copts' representatives acknowledge that Yehoshua's research is thorough and comprehensive, but they disagree with his conclusions.

Yehoshua says the cellar served as a quarry during both the First and Second Temple periods, but during the latter, some of it was used as a burial cave. A structure was built on top by the Crusaders in the Middle Ages, and subsequently a plant for grinding sesame seeds was erected on the premises, which dumped its waste into the cellar.

These were all secular uses, emphasizes Yehoshua. The place was never used for ritual purposes and therefore cannot be considered holy. Moreover, according to the lawyer and his client, since the cellar had been filled with waste since the 12th century, it was not used at all - until the monks showed up under Hirbawi's feet 800 years later.

One of the more fascinating documents Yehoshua found is a religious writ, referring to Saladin, who ruled Jerusalem after conquering the Crusaders: "He dedicated the entire structure known as the House of the Patriarch in noble Jerusalem and all that belongs to it, including the neighboring plot where there is a flour mill ... (and) a large cellar known as the Patriarchs' Hall."

The writ mentions the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. According to Yehoshua, it is valid to this day - and proves that Saladin intended that the shops and cellars be under Muslim ownership. Furthermore, several maps were submitted by the lawyer, the oldest of which is from 1751. The two most important ones to his mind are from the late 19th century and the early 20th century: He says they prove that the cellar was bisected by a wall separating the church premises from the Muslims' property, and adds that the Copts demolished this wall.

For the Coptic Church, this is not just about a cellar. Rather, the dispute is part of a comprehensive struggle to preserve the sect's status as one of the owners of the Church of the Holy Sepucher. In the 1960s, monks belonging to the Ethiopian Church took over part of the Copts' area, and the Copts have accused the Israeli government of collaborating. Since then they have posted guards at strategic points in the church, 24 hours a day. The status quo is so sensitive that it is impossible even to replace a rotted wooden door for fear of violating agreements.

The Coptic Church is a relatively small denomination that lacks political clout and feels threatened by other Christian sects and by the Muslims. The monks fear that losing the cellar will weaken their status in Jerusalem even further.

"The Copts feel discriminated against," says lawyer Gabbay. "They have never caused anyone any harm, and they don't deserve this treatment. The Arabs consider them a tiny minority. They don't even get the rights other churches get in Jerusalem."

The Copts point out that the cellar has stairs that lead up, directly into the heart of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The stairs have been blocked due to disputes among the various Christian denominations. However, their existence proves that the area always has been part of the church.

Mutran Anba Abra'am, the metropolitan of the Coptic Church in Jerusalem, said, "This cellar is part of the historic Byzantine church, the one that was right on top of the Sepulchre. Saladin reduced the area of the church and ordered that the Christians be moved below, leaving the Muslims above. But this is a holy place. How can it not be?"

After going through Israeli courts for several years, the whole matter has now been referred to the minister of religious affairs to determine if the area is indeed sacred - in which case the church would control it - or not, in which case the courts would deliberate the ownership. The current Israeli minister of religious affairs is Benjamin Netanyahu, who is also the country's current prime minister. A decision from his office is expected within the next few weeks.